Travel Wilpena Pound – Wondrous Wilpena Pound

Words: Chrissie Goldrick | Feature image: Chrissie Goldrick

If Australia had its own seven wonders of the natural world, Wilpena Pound would surely be near the top of the list, vying with such luminaries as Kata Tjuta, the Twelve Apostles and, of course, Uluru, which, astonishingly, would fit within Wilpena’s walls six times over. But it’s surprising how many Australians have never heard of, let alone visited, this unique geological spectacle in South Australia’s Ikara-Flinders Ranges National Park.

In fact, visitor numbers to the region have fallen since they peaked in the 1970s, but the Flinders still hold a special place in the hearts of South Australians. Holiday-makers first began coming to Wilpena Pound after it was declared a National Pleasure Resort in 1945. Over subsequent decades, a family camping trip, school excursion or holiday break at The Chalet, now part of Wilpena Pound Resort, became an annual rite of passage for many.

I first set eyes on the Pound in 1999, when I was organising photos for Australian Geographic’s Flinders Ranges guide book. Initially I thought I was looking at aerial images of a massive meteorite crater – the scene of some ancient cataclysm, the indelible imprint of which aeons of weathering had failed to erase. But its origins were a less violent and much more drawn-out affair.

Geologists describe the feature as a “remnant elevated synclinal basin”, and it was once enclosed by far higher mountains. Its steep walls and shallow inner bowl are made of thick layers of super-hard quartzite that have been squeezed along both east–west and north–south axes, forcing the strata upwards and creating the teardrop-shaped 17 x 7km structure. Although time has whittled away several thousand metres from the top of those rippled ramparts, the Pound is still the highest section of the Flinders Ranges.

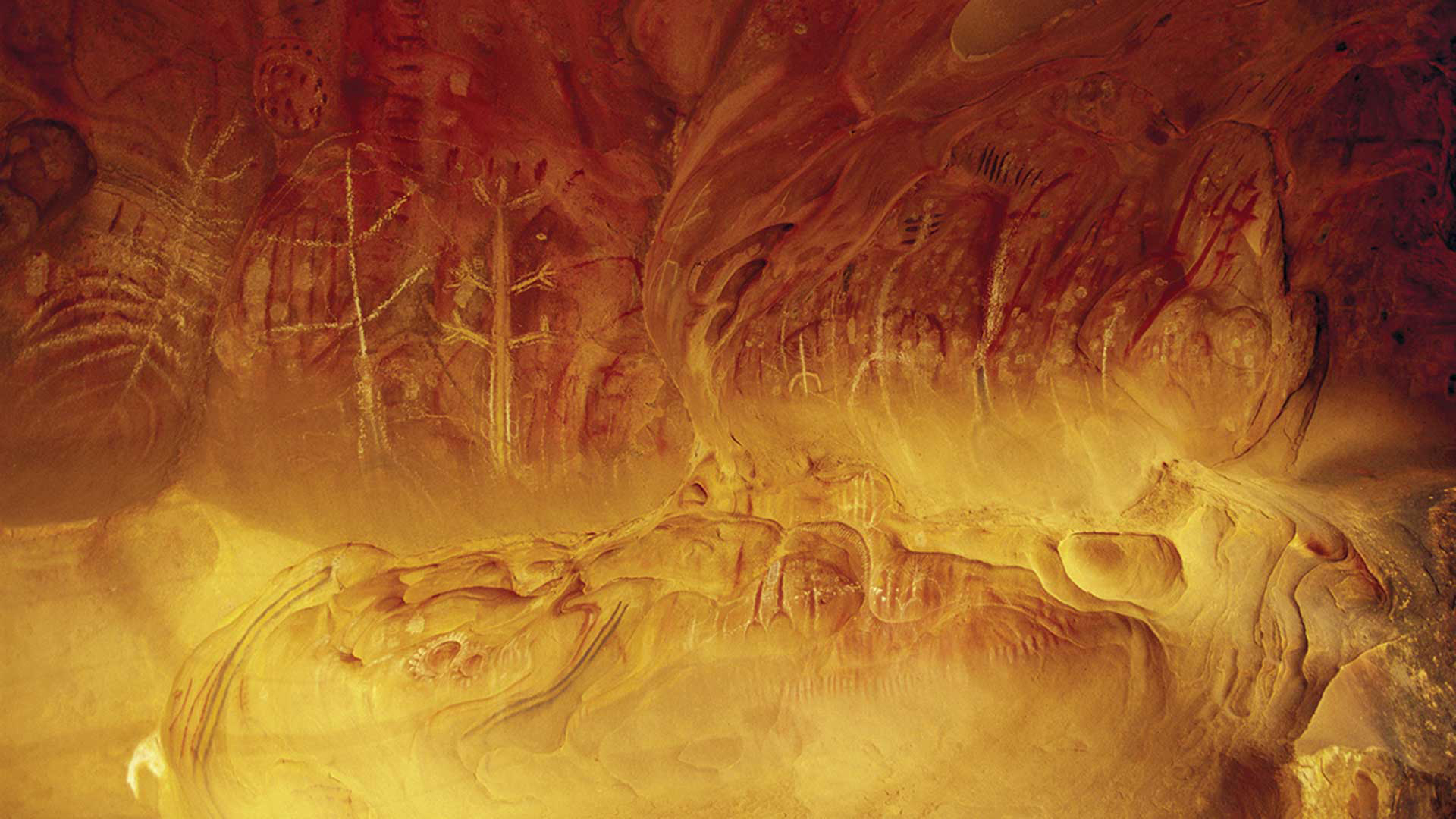

Stories of the Adnyamathanha people are recorded on Arkaroo Rock, a massive boulder at the Pound’s base. Image credit: Mike Langford/AG

The broader Flinders landscape is the result of uneven weathering of alternately hard and soft sections of rocks, with quartzite forming the high peaks and hogback ridges, while softer materials, such as mudstone, siltstone and shale, have been worn away to form valleys and gorges.

In between stand limestone hills striped with darker bands of hard dolomite. Iron oxide lends the rocks a pinkish glow in the half-light of dusk or dawn, and the vegetation here emits terpenes, plant compounds that combine with ozone in the atmosphere to give a tinge of blue to distant vistas.

This vibrant palette of form and colour endows the Flinders Ranges with a beauty and splendour that’s drawn generations of photographers and painters, most notably artist Hans Heysen and photographer Harold Cazneaux (see Snapshot, AG 127), both famous for their use of light.

Long before Europeans arrived, Wilpena Pound, or Ikara (meeting place), had profound cultural and spiritual significance to the Adnyamathanha (pronounced ad-na-mut-na) people, who have inhabited the region for at least 15,000 years. The serpent of their Dreaming stories, Akurra, is Creator and guardian of all permanent waterholes in the Flinders and is said to form part of the Pound’s walls.

Old Wilpena station became part of the national park in 1985. Prior to that, it had been a working sheep station for 135 years. Image credit: Chrissie Goldrick/AG

In 2011, the SA government entered into partnership with the Traditional Owners for the co-management of Flinders Ranges NP. It’s a priority for their stories to be told alongside pastoral and natural histories.

Senior cultural ranger Arthur Coulthard was born under a Flinders river red gum and has worked in the park since the 1980s. He believes strongly that the co-management is paying off.

“People have a better understanding now and I thank my people for doing that, otherwise we would be back in the Dark Ages,” he says. “Visitors to Wilpena have opened their eyes and are really taking on the Aboriginal perspective. This area is a very significant place for the Adnyamathanha because it’s a Dreaming story. We don’t just see the beauty of it; it’s a part of us.”

Wilpena’s modern story began when it was ‘discovered’ by stockman William Chace in 1850 while prospecting for pastoral land for doctors W.J. and J.H. Browne. The pioneering pastoralists took up a number of leases the following year, and, while their sheep flourished, later attempts to grow wheat fell foul of the boom-and-bust cycles that define the lands north of Goyder’s famous line.

In 1920 the leases expired and the government bought back the Pound and registered it as forest reserve. Remnants of two farms are now part of the national park here. Picturesque Old Wilpena station is close to the airstrip and contains restored farm buildings, including an 1864 pug-and-pine blacksmith’s cottage. The Hills family homestead lies inside the Pound and is reached via Wilpena Creek.

This watercourse pierces the encircling walls of the Pound and drains two-thirds of the basin, which acts as a gigantic rainwater collector. Huge, uprooted river red gums lining the creek provide a clue to past deluges, but mostly it just babbles peacefully along.

Image credits: Chrissie Goldrick/AG

There are numerous ways to enjoy Wilpena Pound, but to be truly immersed in this extraordinary landscape you should walk into its very heart, following the meandering creek and its shady river red gums.

“All areas of the Flinders are beautiful, but there are some places that feel almost spiritual…and Wilpena is certainly one of them,” says experienced local guide Tim Tyler. The opportunity to engage with the Traditional Owners here has also enhanced the visitor experience, he says.

“We now have Adnyamathanha guides and staff in the Wilpena Visitor Centre. They greet our guests, who love to talk to the people whose Country this is.”

I ascend the rocky track to the higher of two lookouts on the popular 7.8km Wangara track on a stifling 32°C February afternoon. The thrill of the panoramic view across the Pound’s interior is tempered by an unexpected sensation of peace and tranquillity.

The eerie stillness that seems to permeate the vast enclosure may be the result of the sultry conditions, but I can identify with those who claim a spiritual response. There are a number of official walking tracks, including a section of the 1200km Heysen Trail, all well marked and varying in length and difficulty. The toughest is the St Mary Peak Hike. At 1171m, St Mary is the highest mountain in the Flinders Ranges and significant in the Adnyamathanha Creation stories. For this reason they request walkers finish their hike at Tanderra Saddle rather than continue to the summit. The full walk varies between 14.6km and 21.5km, according to the route taken.

Other tracks lead up onto the rim to peaks such as Mt Ohlssen Bagge, or to the floor of the Pound with its varied animal and plant communities.

In contrast to these close encounters, a scenic flight is almost mandatory in order to see Wilpena in its eye-popping entirety. These take off regularly from the airstrip near Old Wilpena station, and the pilots are experts at avoiding the big red kangaroos and emus that regularly invade the landing strip.

Seeing this country from the air helps to make some sense of its complex geology, but the jagged backbones of the mountain ranges that writhe through the landscape invoke the Akurras, fearsome serpents of the Adyamathanha Creation.

Bush pilots in the Pound have to keep an eye out for emus when taking off and landing. Image credit: Chrissie Goldrick/AG

How to Explore the Flinders Ranges

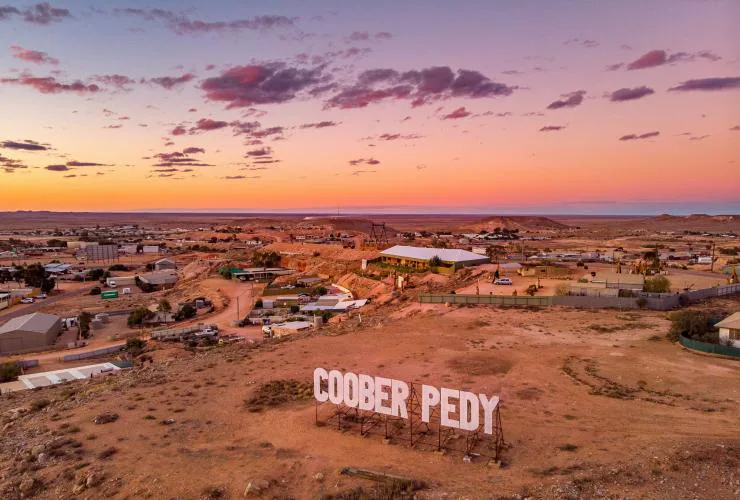

The rugged, weathered peaks and rocky gorges of the Flinders Ranges in outback South Australia form some of the most dramatic and beautiful landscapes in the country. The scenic roads, four-wheel-drive and walking tracks that crisscross the wild expanses take you on a remarkable adventure through 600 million years of history.

THE ESSENTIALS

WHERE: A five-hour drive due north of Adelaide.

WHEN: Bushwalking is much more comfortable in the cooler months. In summer, some trails are closed.

HOW: A two-wheel-drive car can cope with most of the park, but several roads are unsealed. Guided tours are the best bet.

DON’T MISS: A ride on a restored steam train along the picturesque Pichi Richi Railway, built in the 1870s, is a must.