Travel Larapinta – Into the Wilds

Words and images: Cathy Finch

The Larapinta Trail winds through some of the most remote areas of the Northern Territory. Though not a particularly physically challenging walk, its location means respecting a landscape where temperatures can be unforgiving, with extremes of both heat and cold. Water can be scarce so walkers need to be well informed and prepared for unforeseen challenges.

The trail is divided into 12 sections of varying lengths and can be enjoyed as a connected series of day walks, overnight treks, or as a challenging adventure over two or three weeks.

For those who opt to walk unsupported – and there are many who do – care must be taken with pack weights and the planning of itineraries to coincide with food-drop areas. You’ll also need to make yourself familiar with vehicle access points in case you need to leave the trail at any of the trailheads.

“This track intentionally leads trekkers along the tops of high, jagged mountain ridge lines and then dramatically down into remarkable dry riverbeds,” says Tim Sanders, one of our guides on World Expeditions’ six-day Classic Larapinta Trek in Comfort. “It winds through gorges lined with river red gums and out into open woodland forests, showing the huge diversity of the region. Sometimes the morning sections differ entirely from the afternoon, spectacularly showcasing the changing habitats.”

The tour I’ve chosen covers all the trail highlights, while being vehicle-supported so I only have to walk with a daypack and there’s a welcome warm shower and relaxation time when I get to slide my well-travelled feet into cosy ugg boots, while the guides prep a hearty three-course meal under a canopy of stars.

Four semi-permanent camps are spaced along the trail so that each evening a safari-style tent is waiting with a stretcher bed, swag and pillow. I’m travelling with six other people, including three guides, and our first day quickly acquaints us with the sheer size and splendour of the MacDonnell Ranges and provides spectacular views across the country surrounding Alice Springs. We descend into Wallaby Gap where we are met by local woman Rayleen Brown, who teaches us about the native larder of foods and botanicals.

“What you may not realise is this strong connection to plants that Indigenous people have – they still sing songs for the plants today,” Rayleen says. “There is this wonderful 60,000 years of history around food.

“A plant is like a totem – where someone has an ownership of something and must take care of it. It is then handed down to the next generation.”

Rayleen is a Ngangiwumirr and Eastern Arrernte woman who was born in Darwin. “My mum was adopted by the local Arrernte people, never realising that I would become an advocate for the foods and what they taught me in my childhood. It’s great to have a story with food. It’s the essence of things. It’s wonderful to know the answer to the question, ‘Where did this come from?’”

As I dip my damper into some delicious wattleseed dukkah, Rayleen encourages us to try a lavish spread of bush treats, including Kakadu plums, bush tomatoes, lemon myrtle and native capers. She is the founder and owner of a business based on traditional bush foods called Kungkas Can Cook.

“Growing up in Alice Springs we had all different tribal groups living in the town, so kungka was a common word for a lady,” she explains.

Summit of Mt Sonder. Image credit: Cathy Finch

During the following days we witness some of Australia’s most spectacular sprawling vistas. Hard days are followed by easier ones, which helps with our recovery and enthusiasm. The wildflowers we see along the way are stunning. The soft purple pastels of mulla mulla often line our path – particularly pretty when backlit by rays of morning light.

Everywhere the terrain is rich red, rocky, sparse and dramatic. Along the way we build a new and stronger connection to Earth and nature. Who knew, for example, that when you lightly rock a eucalyptus tree you can hear water? It’s like putting a shell to your ear to hear the roaring sound of the sea. You could be forgiven for thinking that if you cut off a branch, water would come rushing out, although of course this is not the case. What we hear is the water within the roots, amplified by the woody tissues of the tree.

Tim tells us about the spinifex, the ghost gums and the First Nations people’s ways of finding and protecting witchetty grub populations. One morning during a spectacular sunrise, rain begins to drizzle and we walk out of camp under the arch of a richly coloured rainbow.

By the end of the day, after the land has drunk in a little moisture, signs of new life have already begun pushing through the soil. Living up to its name, the resurrection fern is among the first to appear.

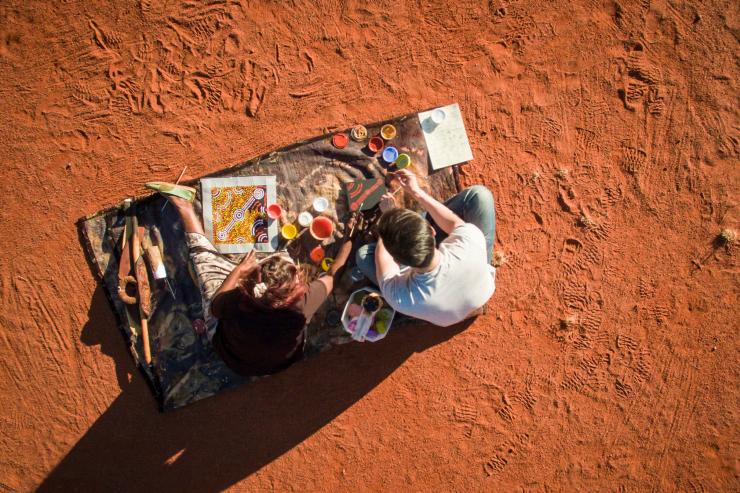

Each day on the Larapinta we experience at least one highlight that takes our collective breath away. Walking through red dirt and granite shingles to sand and boulders, we plunge into ridiculously cold waterholes and roll around in deserted billabongs. We visit the vastly different landscape of the Ochre Pits where First Nations people have extracted and traded ochre for thousands of years.

These pigmented minerals are an integral element to the Dreaming stories of Indigenous people throughout Australia. It’s pretty humbling to be standing before a resource that’s been shared and traded for thousands of years.

Our journey nears its end with a thrilling, heart-pounding crescendo – a 2.15am departure to climb to the summit of nearby Mt Sonder in time to catch the sunrise.

“It’s Friday morning and you are some of the luckiest people in the country,” Tim says, as he prepares to start us off. “Check everything. Run through your gear; be thorough. There’s no coming back. If you’ve forgotten something important, you won’t be reaching the summit.

“You’ve got two minutes before departure. If you changed the batteries of your headlamp yesterday, I want them changed again today. You’ll be walking in pitch darkness. There’s no room for error.”

The excitement is palpable. We walk 8km upwards, to reach 1379m. It’s a tough slog, but all that fades when I come over a peak and the light of the full moon shines down – there is nowhere else in the world I’d rather be.

As the stars fade and dawn breaks, our efforts are truly

rewarded. As if the landscape wasn’t already red and rich enough, the golden rays of light ignite the plains below, dwarfing me to just a speck of dust on the landscape. It’s the beginning of another perfect outback Larapinta day.

Image credits: Cathy Finch, Chrissie Goldrick, Cathy Finch

Today, more than half of Kakadu belongs to the Bininj/Mungguy people, and most of the remaining land is under claim. Traditional Owners lease it to the federal government’s director of parks, so it can be run as a national park under a joint management scheme.

“Our culture is alive and thriving,” Traditional Owner and community leader Jessie Alderson tells me as we shelter from a downpour on the Jim Jim ranger station’s verandah in central Kakadu. Close to half of the park’s permanent staff are Indigenous. “We still keep our practices going, you know, hunting and camping and teaching our young people,” she says.

“Some of the Traditional Owners are the best naturalists we’ve got,” says Steve Winderlich, the park’s natural and cultural programs manager. “They rely on a lot of the native species for food, so they know what’s happening with weeds, for example, because weeds choke habitat for cultural and food species.”

Steve explains how Kakadu’s land-management plans encompass a strong cultural focus. For example, the fire plan, which involves regular controlled burns to reduce fuel loads when spear grass dries out at the end of the Wet, has both an ecological and a cultural component. “The cultural component involves looking at how traditional burning was carried out, but there’s also the impact on cultural sites to consider,” he says. “Fire too close to rock-art sites can exfoliate the rock, and then the art’s gone.”

“Come wet season, like now, the ground’s nice and wet and the weeds start to come up so we’ve got to go out and catch them before they seed,” says Bolmo Deidjrungi man and ranger Fred Hunter.

Fred was born at Madjinbardi (Mudjinberri), a community in north-eastern Kakadu. He completed a parks apprenticeship 26 years ago, and has been a ranger ever since. For more than a decade, he’s been a member of a four-strong team that targets one of Kakadu’s main invasive weeds: mimosa, a woody shrub introduced from Central America. “In the park there are about 300 mimosa plots,” he says. “We have to check each of them at least five times a year. A seed can stay in the ground for 20 years and there’s a risk a pig will come along and dig it up, and you’ll get another plant growing.”

I meet Fred and his team at a point on the road between Jabiru and Gunbalanya (Oenpelli) where the bitumen is covered in water, and Fred launches the Swamp Master.

The roar of the airboat’s huge fan thunders across the watery landscape as we plane along the submerged highway. We’re heading for Marnanj, the Magela Creek floodplain, where Fred and his team will check mimosa plots on the Djarr Djarr billabong. “During the wet season we use airboats and helicopters to check plots,” Fred says. “In the dry season we go out on quad bikes. We go everywhere. Wherever mimosa grows, that’s where we go.”

Larapinta Trail. Image credit: Alan Dixon

As we jet across the billabong, a large white cloud mass starts spitting rain. The escarpment makes for a dramatic backdrop, and from this vantage point, as we swerve around the tips of submerged termite mounds, the power and sheer scale of Kakadu’s dramatic Wet-Dry cycle really hits home. In a matter of months, this expanse will be a stretch of dry savannah woodland. I’m glad I’ve seen Kakadu’s ever-changing landscape at its wettest.

I recall my conversation with Sarah Kerin. “I would definitely recommend people come twice,” she’d said. “There’s nothing more beautiful than looking up over the escarpment at a canopy of stars on a dry-season night. Or simply going out and walking around Anbangbang Billabong on an early dry-season morning when you have the mist and you can smell the swamp and the lilies. It’s just beautiful. During the wet season the park is entirely different. It’s characterised by rejuvenation and a refreshment of the landscape.”

How to Explore the Red Centre

There are several ways to experience the ancient land-scapes, raw beauty and unique geological features of the Red Centre. There are multi-day hikes for the self-sufficient or supported by a range of trekking companies. Try the overnight Giles Track (22km) at Kings Canyon. The Larapinta Trail in the West MacDonnell Ranges is accessed from Alice Springs, while other highlights can be enjoyed from Yulara, the township situated just outside the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. Yulara’s airport services flights from all major cities.