Travel East Gippsland – An Island In The Sky

Words: Quentin Chester | Images: Don Fuchs

The crown of Mealing Hill is barely 100m off the main access track in Coopracambra National Park.

The 528m-high bald knoll serves as a handy lookout; in fact, after a day roaming forest-shadowed tracks on Victoria’s far eastern border, the view’s a heart-stopper. Suddenly there’s clear sky galore and a sea of green spreading to every horizon.

Many stirring features set East Gippsland apart: roiling rivers; a throng of mountains, lakes and wetlands; flood-cut gorges; and a far-flung coast of dunes and headlands. Yet the living force that draws the region together – and stalks your every move – is tall timber.

More than 75 per cent of the shire’s 21,800sq.km bristles with forests, both ancient and modern. Their presence defines this natural stronghold and the people who carve out a hard-won life here. North from Mealing Hill, the view spills across forested ridge tops in a smoky blue haze. On paper Coopracambra NP marks out 38,800ha of wilderness, including the largest warm temperate rainforest in Victoria. However, as with so much of East Gippsland, the human-drawn boundaries seem arbitrary. In truth this park’s patchwork of forests just keeps rolling across the New South Wales border all the way to the Monaro Tableland.

To the south, Coopracambra NP appears to blend just as seamlessly with woodland extending 40km to the coast. Look closer, however, and clear-felled slopes are plain to see. Elsewhere the tree cover seems thinner and unusually uniform. This is regrowth forest, a legacy of the logging industry. You soon learn that in this neck of the woods, there are forests and then there’s old-growth.

Errinundra National Park is an island in the sky, a 1000m-high plateau that snags clouds pushing inland from Bass Strait. To walk this lofty 25,600ha kingdom is to confront the gifts of antiquity. Here the wet eucalypt forests are home to mighty shining gums and cut-tail eucalypts – many more than 400 years old. The park is also one of Australia’s outstanding havens for cool temperate rainforest.

At ground level, among the filigree of ferns and vines, there’s a damp stillness to the filtered light. All around, the forest echoes to the trills and chirrs of lyrebird song. Every now and then among the moss-smothered trunks there appears a pale, massive, milky-grey column: the unmistakable tower that is a shining gum.

The isolated headland at Cape Conran is spiked with 470-million-year-old rocks

Long-time forest defender Jill Redwood has lived close to the plateau since 1980. For her the ancient forests are a potent link to a forest grandeur before European settlement.

“When you’re sitting under one of these enormous gums it really puts you in your place,” she says. “It’s awe-inspiring. From giant trees to the smallest lichen growing on their bark, the diversity – and all the interactions – is just amazing.”

Errinundra NP has more than 700 different types of plant. No fewer than eight possum and glider species call these tree canopies home. The park is also a refuge for the threatened long-footed potoroo and spotted-tailed quoll, not to mention about 140 bird species, including six types of owl. All this is but a hint of the richness only old-growth forests can nurture.

The diversity at work deep in old-growth forests is also writ large on landscapes unfolding across East Gippsland. Less than 20km north-west of Errinundra’s dripping-wet canopy, everything changes. As McKillops Road dips down towards the Deddick River, fern-filled valleys give way to scraggly slopes of white box and white cypress – dry-land trees that mark a twist in the tale.

There’s much more to the imposing Snowy River National Park (1145sq.km) than its fabled waterway. The bulk of this expanse is a tangle of outcrops and ridges cloaked in alpine ash forests and cut by remote tributaries such as the Rodger River. Such is the dominance of these highlands over south-westerly weather that they cast a permanent rain-shadow over the country around McKillops Bridge.

Little has changed on the narrow, crumbling tracks that snake into the valley on both sides of the river. Driving this road remains an authentic overland adventure – not least for the chance to cross McKillops Bridge. Spanning 250m and poised 15m above the river below, this hidden marvel of Depression-era engineering is a classic timber stock bridge held aloft by concrete and steel supports.

To hear the bridge’s thick wooden deck rumble under the weight of rolling wheels is to connect with a sound that’s echoed for generations across East Gippsland’s rivers. While the Snowy’s modern flow is piddling compared with the days when the bridge was built, the surrounding country still packs a wallop.

For most of its run through Victoria, the Snowy is tucked out of sight in deep valleys and ravines, such as

Tulloch Ard Gorge, where a new walking track descends through wonderful messmate and stringybark forest to a lookout perched atop the gorge entrance. Here the river is but a slender ribbon of water wedged between mighty cliffs and timbered spurs.

Lake Barracoota and the beaches of Telegraph Point typify the wild East Gippsland coastline.

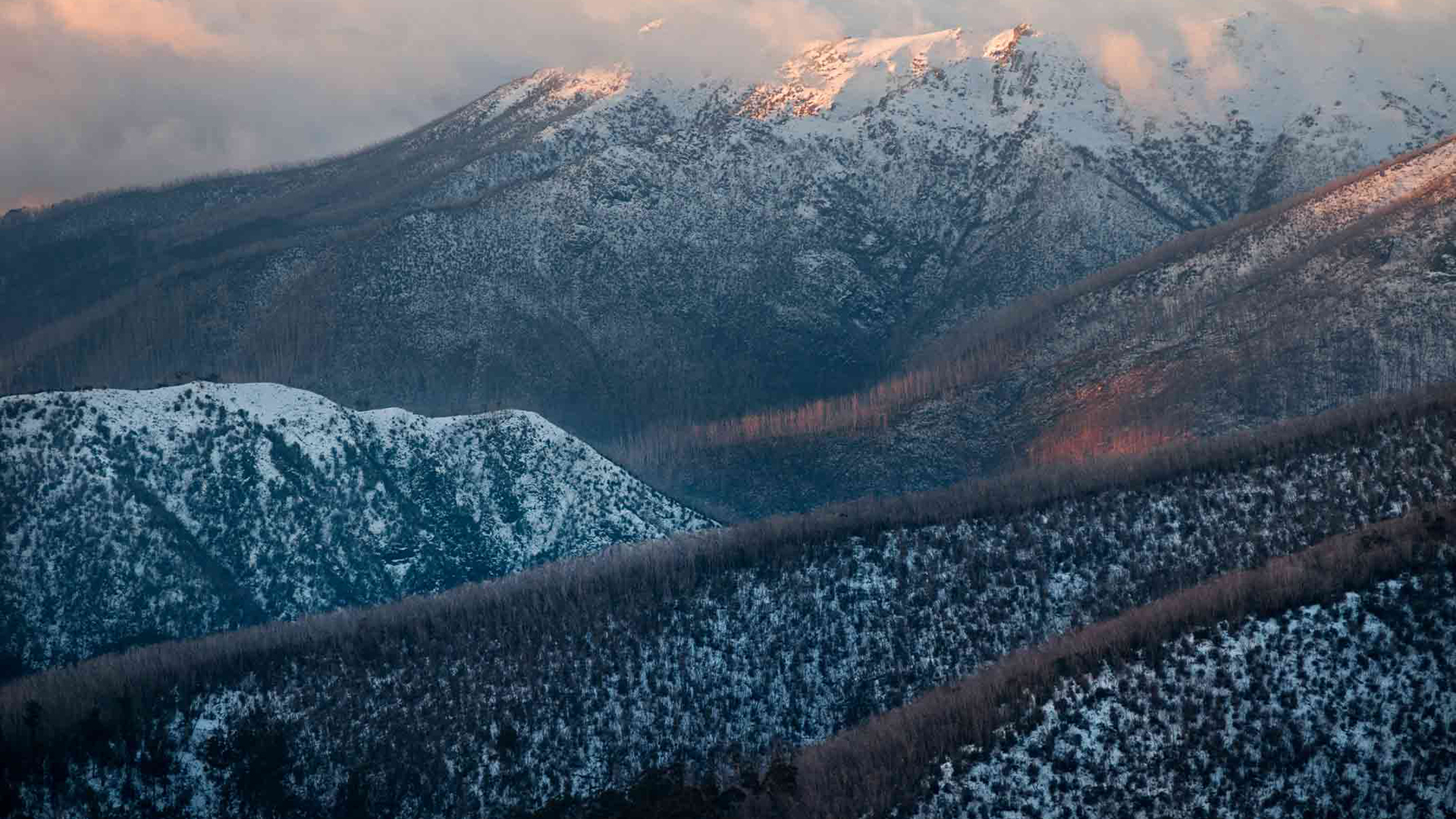

The natural barriers that feed East Gippsland’s mystique straddle the Great Divide and keep going. Alpine National Park – Victoria’s largest, at 6460sq.km – is a high-country archipelago fortified by imposingly tall mountain ash forests. Higher still, where winter brings a crusty cap of snow, bare ridge tops are fringed with snow-gum woodland.

Mt Loch is just such a feature, a mere blip on a ridge just north of Mt Hotham’s busy ski resort. On a clear day, however, the view north from Mt Loch takes in one of Australia’s most sharply etched peaks, 1922m-high Mt Feathertop. After a flurry of winter storms, this ravishing summit – Victoria’s second highest – is plastered in a wind-blown cornice that dangles precariously over its eastern flanks. There’s really nothing else remotely like it on the mainland.

Just below the summit of Mt Loch is a small patch of snow gums. Ancient, ice-caked and contorted by the elements, these are arguably the most stoic and vividly hued of all the eucalypts. This patch is extra-special because it’s among the few in the region that are intact.

In the space of just three years, Victoria’s High Country was ravaged by two of the most brutal bushfires southern Australia has ever known. The first, in January 2003, burnt 12,000sq.km. The second, which took hold in December 2006 and raged for 69 days, wiped out about 11,000sq.km, including large tracts of country that had been charred only a few years earlier.

Yet tiptoe off Mt Loch to the edge of the snowline, and more affirming signs await: new growth sprouting on the snow gums and mountain ash, gurgling creeks feeding into the Diamantina, plus East Gippsland’s ubiquitous ringtone: lyrebird serenades.

Bushfires have scant regard for any barriers, natural or otherwise. From the highest peaks to the humblest coastal heath, this is a region where fire is like a fifth season. Ask ranger Phil Reichelt from Parks Victoria at Mallacoota. His patch covers the far eastern quadrant of Victoria, including national parks such as Coopracambra and Croajingolong, an outstanding Biosphere Reserve with a lavish smorgasbord of coastal habitats extending 100km from Cape Howe.

On a map as big as a picnic rug, Phil has marked an intricate quilt of areas on his beat that are variously burnt, unburnt and slated for possible fuel reduction. It’s a daunting patchwork to look after, but given all the attractions on his doorstep – from offshore islands to highland forests – the task has its compensations.

“If you look from northern NSW to Wilsons Prom, it’s really only this corner of the world that’s truly wild and offers this variety of experience,” says Phil. “Put it this way: I came here in 1987 for three years, and I’m still here.”

Errinundra NP’s bountiful old-growth forests boast more than 60 species of fungus.

One of Phil’s favourite haunts is a 1km walk east along the ocean beach from Mallacoota Inlet. Just past tiny Tullaberga Island you scramble up the dune face and onto a vast sand blow. On the horizon stands Howe Hill and spread before you at your feet is Lake Barracoota. Here the sound of the breakers gives way to frog song, red wattlebirds gabbling in the banksia scrub and trumpeting black swans out on the lake.

It’s a captivating hideaway created by thousands of years of shifting sediments and sands isolating an eastern arm of the inlet. Among the nearby dune swales are scattered shell middens and stone tools left here by the Bidawal people. Before this lake was a lake, and long before the advent of bullock drays and dashing blokes on horseback, the entire region was country where First Nations cultural groups lived and worked. From the gatherings to feast on bogong moths near Mt Feathertop to those who met for a feed around Lake Barracoota, it’s always been a place of bounty. On these shifting sands the continent turns a corner, east meets south, mountains merge with forests. Excited rivers run free to the sea. In the continuing struggle for its preservation, East Gippsland is emerging as an immeasurable gift, a land where the past is vividly present and old growth seeds new hope.