Travel Boodjamulla – Ancient Oasis

Words: Hannah James | Images: Don Fuchs

A journey into the past can take a lifetime – or a heartbeat. We’re walking into the unknown, up a hill no-one has climbed for perhaps decades, per-haps centuries. As we skirt tussocks of spinifex and clusters of eucalypts, acacias and figs, aiming for a soaring red cliff, Jarrod Slater, a First Nations ranger at Boodjamulla National Park, in north-western Queensland, is optimistic we’ll find fragments of the past we’re looking for.

“Life wasn’t that different back then – still had to eat, still had to drink water,” he says of his ancestors, traces of whose presence we’re searching for in this remote section of the park. “Instinctively, I’d go to that valley – there’s shelter, a load of food and water. We aren’t that different from the Old People.” The place we’re heading for appears to have the essential elements for life – and more: “If you were camping right up there, you’d feel pretty safe with an 80–90m cliff behind you. It’s a good lookout, too.” We’re seeking evidence of First Nations people in an area of Boodjamulla where features are unnamed, except in the unofficial rangers’ argot (Gaffer’s Knob, the Great Wall of China). Our highest hope is to find art on the towering rock walls.

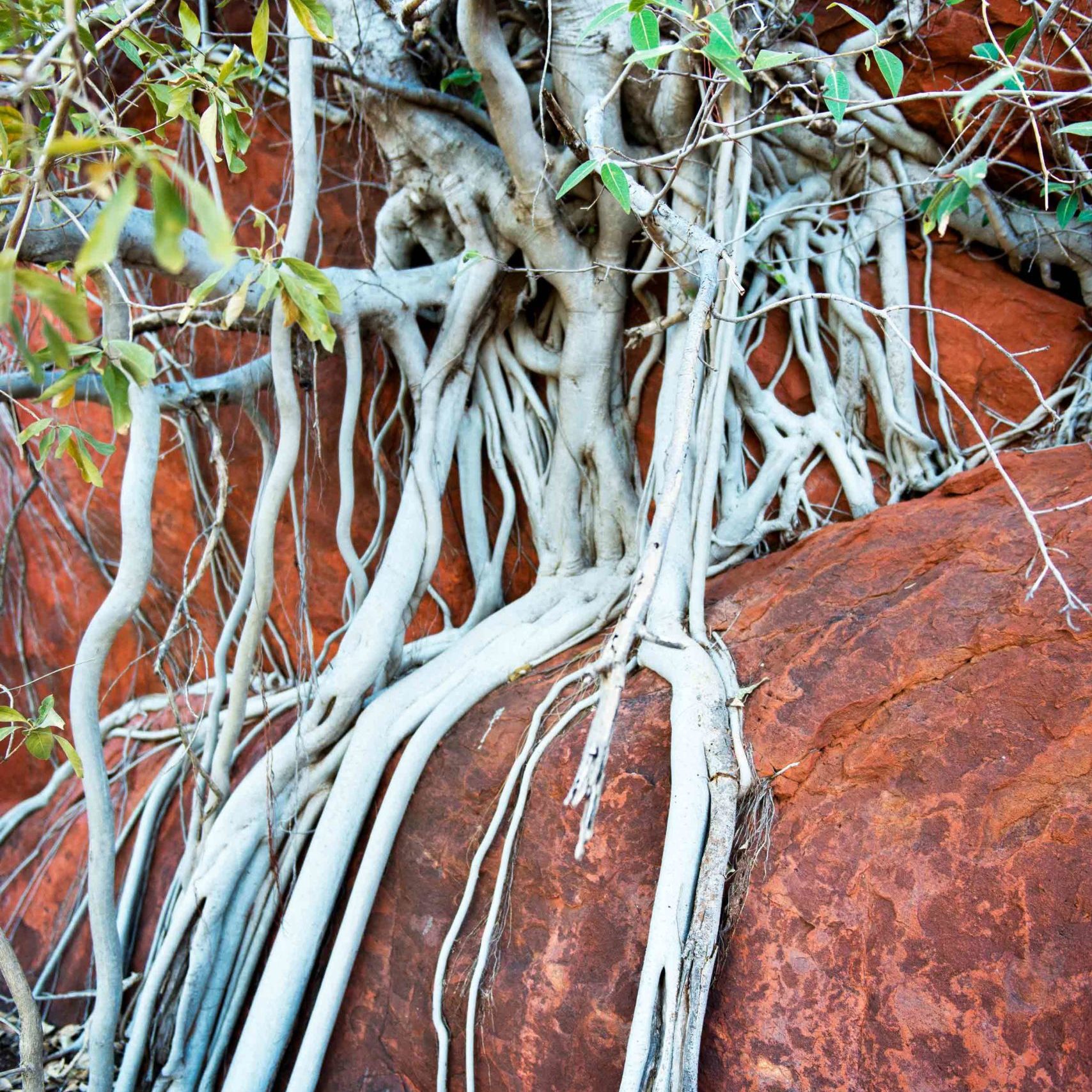

Ridgepole Waterhole (above) is one of ranger Jason Bruce’s peaceful spots, a place of refuge from his duties in Boodjamulla NP. Although stray cattle can occasionally trample its banks in search of water, the waterlilies shine on. Trees cling along the edges of Lawn Hill Gorge (right), their roots snaking to the water over vividly coloured rocks.

Bush-bashing into the wilderness, I feel like stout Cortez in the Keats poem, staring out “with a wild surmise” to find potential new realms of gold. But reality keeps intruding on the poetic ideal. Spinifex, as its name suggests, is very spiky. As we crash through clumps of the stuff, it’s this quality that most impresses itself painfully upon me, despite my guide’s enthusiasm for its other notable properties. “We use spinifex resin for gluing stone tools together,” Jarrod says. “I keep some in my truck. I’ve done a lot of work with stone tools with an old man I worked with – we had 30 men from Africa come to see how it’s done.” As we walk, he hands me a leaf: “It’s soapbush – here you go, rub a leaf of this between your hands and it lathers up, washes your hands.” I learn about the medicinal properties of certain eucalypts: “Crush the leaves, boil them in water and use it as antiseptic wash”, and of the sandpaper fig: “It eases skin irritations – you rub it on itchy bits.” The bush isn’t just a medicine cabinet – it’s a larder, too. Jarrod points out bloodwoods: “There’ll be heaps of witchetty grubs in there,” he says. Then he sees some snappy gum: “You can soak the gum in water and eat it – that keeps you chewing for a while.” He moves through the bush with grace and I glimpse an almost-vanished world where the locals’ knowledge of nature allows it to provide food, medicine, shelter and tools. “It’s a culture that’s run strongly for tens of thousands of years,” says Jarrod, a Waanyi man whose family is recognised on the native title of which Boodjamulla (formerly known as Lawn Hill NP) forms part.

These ripples were etched in sand by an inland sea that existed an extraordinary 1.56 billion years ago.

As we near the cliff, clambering along a rocky creek bed, we return to the present, scanning the wall for art and the base for artefacts or other indications of Aboriginal presence.

There’s a trickling fall of water clustered with ferns, and stones at its bottom that dam the flow to create a limpid pool. It isn’t clear if the stones were placed there by people or grouped by nature – and although we beat along the bottom of the cliff as far as we can, clambering around clumps of trees, over rocks and through bushes, dodging snakes and spider webs as we go, we don’t discover any other signs of habitation. It’s a disappointment, but as we scramble back down the hill towards Jarrod’s truck, we’re not thinking of what we didn’t find, but what we did. “I can’t imagine anywhere I’d rather be,” Jarrod says. “I feel like I’ve found my calling.”

Boodjamulla NP is a sparkling oasis in the outback’s Gulf Country, located 325km north-west of Mount Isa on Queensland’s border with the Northern Territory. The spectacle of the glowing red sandstone of Lawn Hill Gorge, which 1.56 billion years ago was a shallow seabed, is what draws most visitors. Walk along the edges of the gorge and you can still see ripples cutting into the rock, etched by waves that washed over the sand in a world where the only living things were bacteria.

Left: Cobbold Gorge is known as QLD’s narrowest, being barely 2m wide in places.

Right: Normanton, QLD, a former goldmining town, is a historic highlight on the Savannah Way.

The turquoise waters of the gorge are rich in calcite, which, when it flows over objects left in its path such as fallen tree trunks or rocks, forms calcium carbonate, which in turn forms a brittle rock called tufa, a form of limestone. Indarri Falls is made of tufa, as are the Cascades. In this way the gorge is still being formed, moving and changing faster than the almost infinitely slow heart-beat of geological time usually allows. Gliding silently up the gorge in an electric boat is like entering a little Eden – a uniquely Queensland take on the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. The roots of fig trees snake down to the chalky turquoise water; ghost gums, Leichhardt trees and pandanus squeeze into crevices, clinging to life. A sunbaking turtle gently slides off a rock as the boat approaches and silently sinks beneath the water. It’s a Gulf snapping turtle (Elseya lavarackorum), which hasn’t changed in appearance or behaviour for 25,000 years. The gorge is rich in other life, too. Agile and rock wallabies sure-footedly navigate its steep slopes. Cormorants and egrets cruise the waters looking for archerfish, triggerfish, barramundi, bony bream and sooty grunter. Freshwater crocodiles relax by the falls when there’s no-one around, vanishing as soon as they hear a voice or a splash.

Sitting on a sun-warmed rock beside the falls, I can hear children laughing as they tumble in and out of their canoes, and the distinctive chittering of purple-crowned fairy wrens. Unruly mobs of lorikeets arrow overhead, and the clean, cool scent of falling water cuts through the smell of the hot dust. It’s a scene of tranquillity that head ranger Jason Bruce is keen to preserve.

As Boodjamulla’s ranger-in-charge, Jason is responsible for the management of the entire 2820sq.km park, as well as the safety of its many visitors. “We’ve got 18 canoes at the moment to hire out, and one electric boat. That’s plenty – I don’t want to spoil the ambience,” he says.

Jason is an outback Santa, white beard and all, a big man with a bigger laugh that can surely be heard across the length and breadth of the park. He’s a jacka-roo-turned-carpenter-turned-park ranger, who as a child was once found poaching eels by a stranger. Terrified of being punished, little Jason told the man to bugger off. That stranger happened to be American country music legend Johnny Cash, come to play a gig. Jason is full of homespun sayings, many gleaned from his grandad, who he remembers was always “staring at you over the top of his bifocals with his log-cabin durries, drinking hillbilly tea”.

CATTLE CoUNTRY

More than 43,000 people visit this World Heritage-listed national park annually, most to behold the beehive domes of the Bungle Bungle Range – fragile formations eroded over 20 million years.

Amazing as they are, there’s a lot more to uncover in the wide expanses of the Kimberley region. Take water, food, fuel and other supplies: this area is remote with limited supplies available and mostly untreated bore water, which is unsuitable for drinking.